Wrangling Words: Microsoft Word and Creative Thinking

This is the second article in a series focused on how software shapes our thinking. The first article in the series, Software Tools, Creative Thinking, And Craft Workflows, introduced my goals for the series and the concept of “craft” workflows—personalized toolkits and modularized workflows that privilege creativity over efficiency. Craft workflows are the opposite of the standardized approaches to software and workflows that inform the design of the most popular applications and suites. This week’s article looks at the evolution of word processing software and Microsoft Word for insights on why popular applications often become walled gardens for creative thinking.

You may already be familiar with the writer Steven Johnson. He’s the author of several best-selling non-fiction titles, including Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation, How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World, and Everything Bad Is Good for You: How Today’s Popular Culture Is Actually Making Us Smarter. Johnson’s first book was Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate. Published in 1997, the book was one of the first written for the public that looked at how software interfaces were changing the way we think.

Here’s Johnson reflecting on how his first experiences with a word processor affected his writing:

It was a subtle change, but a profound one nonetheless. The fundamental units of my writing had mutated under the spell of the word processor: I had begun by working with blocks of complete sentences, but by the end I was thinking in smaller blocks, in units of discrete phrases. This, of course, had an enormous effect on the types of sentences I ended up writing. The older procedure [writing longhand using pads of paper] imposed a kind of upward ceiling on the sentence’s complexity: you had to be able to hold the entire sequence of words in your head, which meant that the mind naturally gravitated to simpler, more direct syntax. Too many subsidiary clauses and you lost track. But the word processor allowed me to zoom in on smaller clusters of words and build out from there—I could always add another aside, some more descriptive frippery, because the overall shape of the sentence was never in question. If I lost track of the subject-verb agreement, I could always go back and adjust it. And so my sentences swelled out enormously, like a small village besieged by new immigrants. They were ringed by countless peripheral thoughts and show-off allusions, paved by endless qualifications and false starts. It didn’t help matters that I happened to be under the sway of French semiotic theory at the time, but I know those sentences would have been almost impossible to execute had I been scribbling them out on my old legal pads. The computer had not only made it easier for me to write; it had also changed the very substance of what I was writing, and in that sense, I suspect, it had an enormous effect on my thinking as well.

(Emphasis added)

Johnson beautifully describes the way writing on a computer changed his process and ultimately his thinking. Notice how he talks about the impact word processing had on his units of thought (from sentences to blocks of text) and how it changed his sentence length and structure (from shorter and more direct sentences to longer, more complex sentences). These are the kinds of insights we’re looking for as we try to develop a more nuanced understanding of how our software tools shape our thinking processes.

From Word Processing to Document Processing

Here’s a screenshot of the first version of Microsoft Word for the Macintosh, launched in 1985:

Microsoft Word 1.0 for Macintosh (1985): Source winworldpc.com

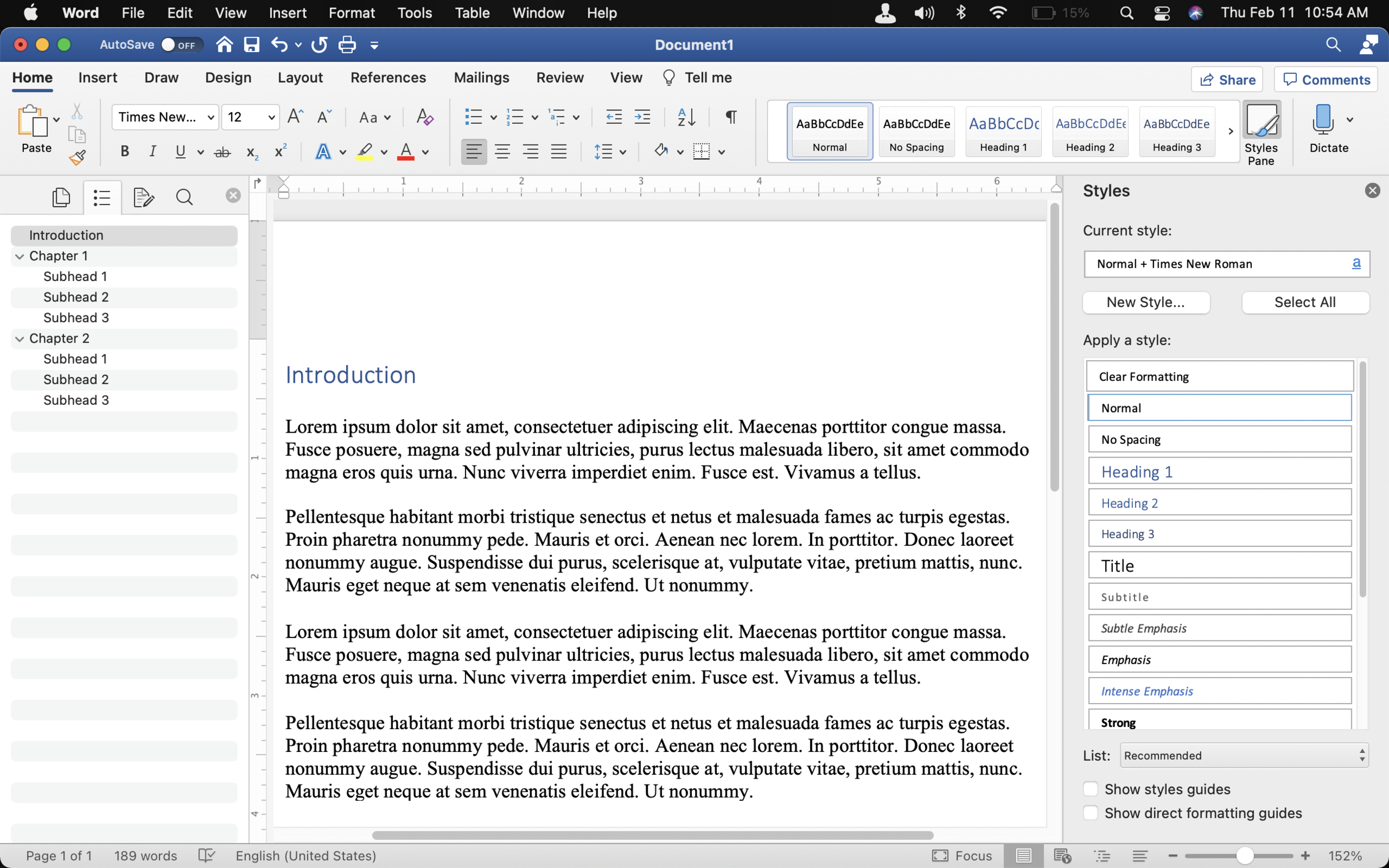

Here’s how Microsoft Word for the Macintosh (version 6) looked in 1997, the year Johnson published Interface Culture:

Microsoft Word 6.0 for Macintosh (1995): Source winworldpc.com

Skip past the differences in screen resolution and the addition of color. For our purposes, the important changes are:

The expansion of the application menu options, including new View, Insert, Format, Tools, Table, and Window menus.

The addition of the two toolbars, with the top bar primarily focused on editing and content integration features, and the lower one primarily focused on styling.

The addition of the rulers, tools that sharpen the focus on page layout.

(Note that many of these features appeared in Word well before version 6.0. I included a screenshot of version 6.0 because it was the current version when Johnson was writing his book.)

And here are two screenshots of the current version of Microsoft Word for Mac (version 16, first released in 2015):

Microsoft Word for Mac Version 16.45

Microsoft Word for Mac Version 16.45 with the Navigation and Styling sidebars open

Notice the continued expansion of the menu system and the more prominent placement of the styling features in the toolbar. There’s even a Layout menu now. The second screenshot of the current version shows you what the application looks like with the Navigation and Styling sidebars open. These features expose the hierarchical skeletal structure that sits just below the writing surface of a Word document. While it’s certainly true that most writers use hierarchies to arrange content (meaning that sections of content are “above,” “below,” or at the same level as adjacent content), Word is optimized for creating, visualizing, and managing content that’s organized hierarchically. Ideas in Word are ordered and ranked.

These screenshots show you how Word evolved from a writing tool to a structured document processing tool, but this evolution wasn’t inevitable.

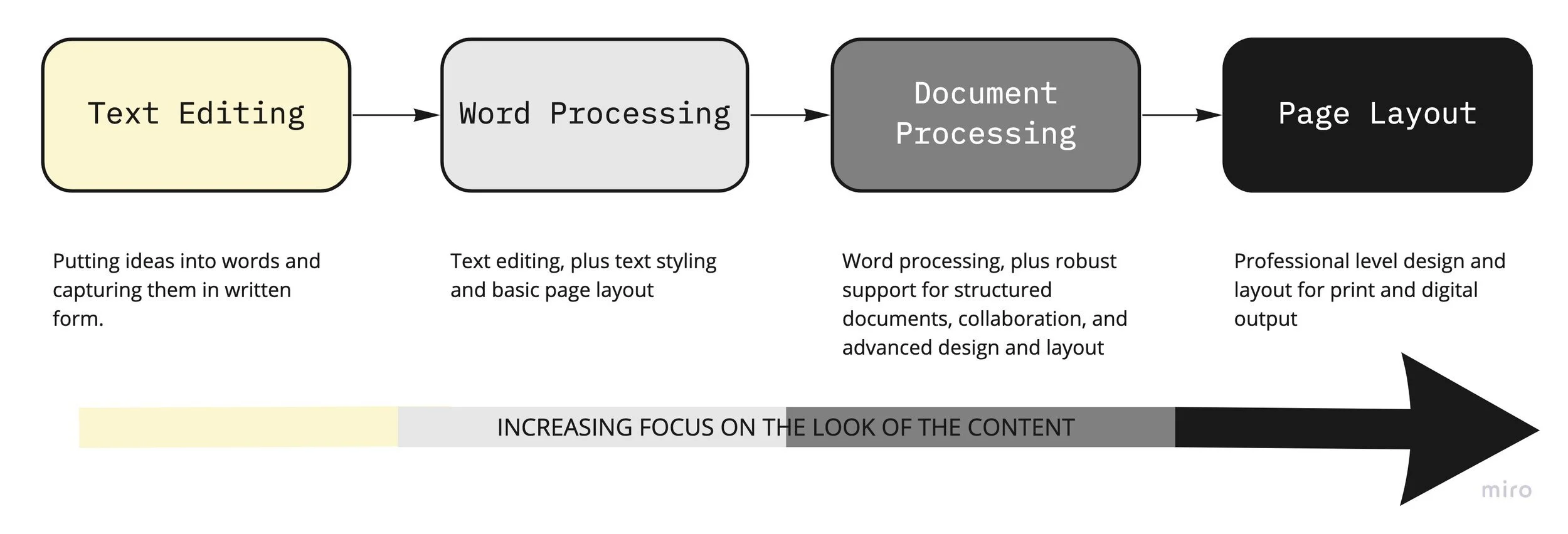

The Evolution of Word Wrangling Tools

The first writing tools for computers were text editors, simple programs that enabled programmers to write and edit “plain” text—text without any styling. As the capabilities of computers evolved, the representation of text on-screen and in the system also evolved. Plain text morphed into “rich” text that’s stored in the system with information about the size of the text, style (italic, bold, etc.), typeface and so forth. Text editors also evolved. A new class of writing tools, referred to as word processing tools, gained the ability to style text and control the basic elements of page layout (such as margins and indentation).

While word processors were more complex than text editors, their primary focus was still “wrangling words”—creating and editing text. These tools were sophisticated enough to enable writers to produce a good-looking business letter or simple report, but they weren’t robust enough to produce a professionally designed and produced book, magazine, or brochure. Producing “professional” quality publications still required the services of a skilled designer and the use of a desktop publishing tool like PageMaker or QuarkXPress. For the most part, this is still true. What’s changed is that the design and layout capabilities of Microsoft Word have become much more robust, making it a viable production tool for many projects that would have previously required the use of a desktop publishing tool.

The diagram below illustrates how Word’s focus on enabling the production of more sophisticated documents has pulled it further and further from being a writing tool toward its current position as a document processing tool.

As Word has increased its focus on producing “professional” publications, the cognitive overhead of using Word has also increased. Compare the amount of screen real estate the toolbars and other visible controls use in Word 1.0 vs. the current version—it’s no wonder that many writers feel their words get lost in the latest version of Word.

(Note: Microsoft Word is very customizable. You can customize, or hide, the toolbars, rulers, and other chrome around the page, but when you need to use one of the hidden features or tools, you’re still confronted with an overwhelming number of options. Learning and using Word is a challenge for many people.)

The merging of writing and presentation tools has pushed all kinds of production decisions on authors, who are now asked to make design and layout decisions, proof their work, and decide on the best formats for distributing their work. Word tries to “intelligently” assist with more and more of what were production processes—and they do a decent job. A writer with limited production skills can produce a nice-looking document using Word’s templates, themes, and design tools. Word’s grammar and spell checking tools catch a lot of common mistakes. But because the process is standardized, the output is standardized too—the editing choices, design choices, and layout choices are constrained by rules-based logic. Word gives you lots of choices, but it’s still a walled garden.

To be fair, Word is a great tool for many knowledge workers. It’s relatively easy to produce a nicely designed report without the support of a skilled production team. That said, I believe Word is no longer a good choice for creative writing. There are better tools for wrangling text that have less structured approaches to writing and require less mental energy.

Beyond the Walls

A lot has changed in the 20 years since Johnson published Interface Culture. Certainly the biggest change has been the role the internet plays in our personal lives, work, and culture. The internet has also changed how we think about text and the artifacts of our engagement with the written word (messages, letters, stories, books, and so forth). Text and the work we produce have transitioned from being static (printed documents, reports, research papers, books, etc.) to being dynamic (tweets, blog posts, websites, etc.). Word was designed in a world where most text based content was printed, packaged, and shipped. Today, most text content flows—it’s liquid. We’ve traded control over the appearance of our work for instantaneous, global distribution of our work via the Internet to a never-ending range of digital devices. If Word looks and feels “old,” it’s in part because the work products it’s optimized for are no longer as central to our experience as they were 20 years ago. Word isn’t the tool you use to write a tweet, it’s not the tool most people use to blog, or write email, or even write essays and research papers for school. The mental models that informed the design of Word are no longer as central to our culture as they once were. There was a time when Word felt empowering; today it feels like an out of style business suit.

In Craft Writing Tools I introduce a few alternatives to Word.