Choreographing Creative Thinking

Let’s begin with a quick breathing exercise: Get comfortable wherever you are—standing, sitting, or lying down. Relax your body. Now, inhale through your nose, pause for a moment, then exhale slowly through your mouth. Focus on your breathing. Feel your chest expand as you inhale and contract as you exhale. Repeat this exercise five times.

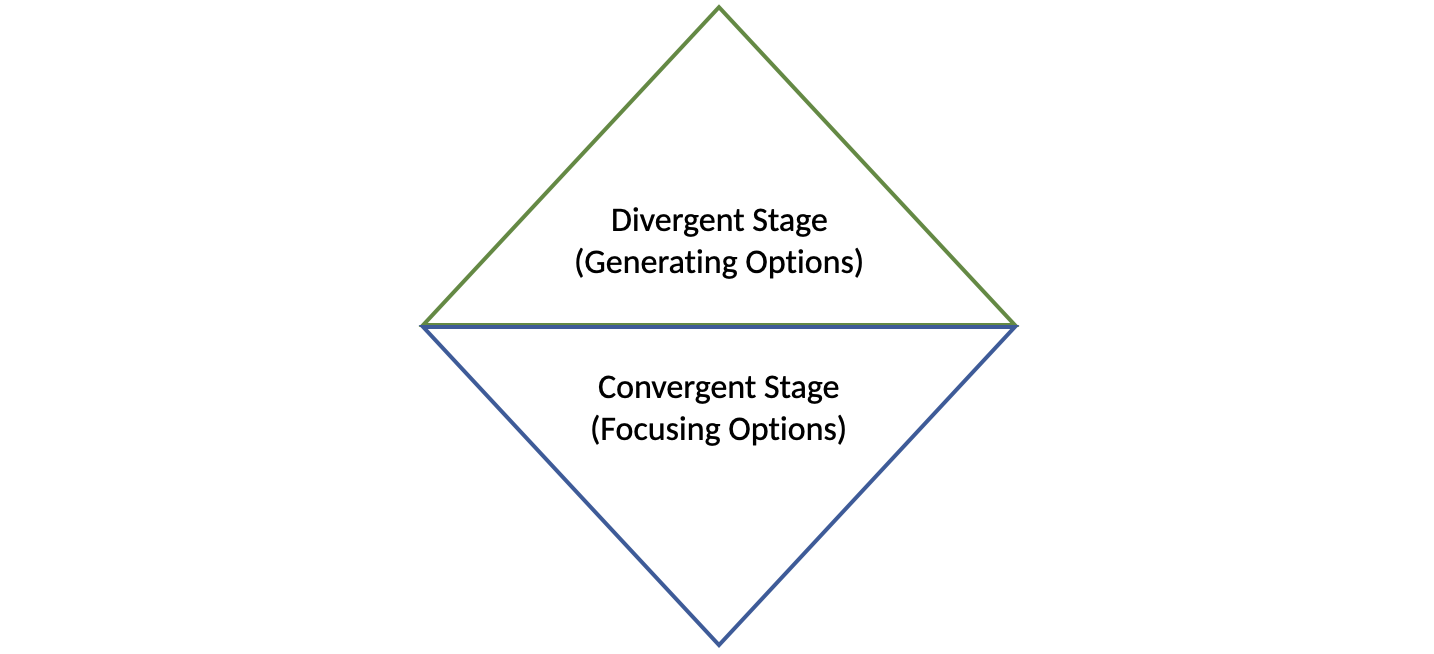

Now think about your mental model of the creative process. What shape does it take? How would you draw it? There’s a good chance the image that comes to mind will look something like this:

Visualization of the Basic Flow of the Creative Problem-Solving Process

You may have seen this diagram before, but even if you haven’t, you may have pictured something similar. Why? Because it’s a visual representation of the deep breaths you just took—a model of a process of expansion and a contraction. The photographer and writer Sean Tucker starts with the word “inspiration” and traces it back to its Latin root “inspiratio,” which means “drawing in of breath,” or “being breathed into by the Divine.” He says, “Like the air we breathe, we need to draw in our energies, our message, our ideas, even our motivation to make new things.” We need to take a deep breath in before we can speak out.

The terms divergent and convergent thinking were introduced in 1950 by the American psychologist J.P. Guildford. He used the terms to define two distinct problem-solving mindsets:

Divergent thinking: Focused on generating many potential solutions to a problem.

Convergent thinking: Focused on reaching one well-defined solution to a problem.

Visualization of Divergence and Convergence

Recent research on the design and functions of the human brain has given us new insights into the neural networks that support divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking is connected to mind-wandering, the default state of our brain that’s “marked by the flow of connections among disparate ideas and thoughts, and a relative lack of barriers between senses and concepts.” (Daniel J. Levitin, The Organized Mind).* Convergent thinking is driven by the central executive mode (also known as the executive functions), the neural network that focuses our attention and keeps us on task. These two functions are mutually exclusive, but creativity demands that we choreograph a dance between the two functions. That dance is the focus of this article.

The Dance Between Divergence and Convergence

In 1928, Alex Osborn and three other advertising executives created Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn, more commonly known as BBDO, now the world’s largest advertising agency.** Osborn was a very successful executive, but his passion was understanding the creative problem-solving process. In his book How to Think Up, published in 1943, introduced the concept of “brainstorming.” In 1952, he published Applied Imagination, which included his first attempt at a comprehensive description of the creative process. The seven steps Osborn identified are:

Orientation: Pointing up the problem.

Preparation: Gathering pertinent data.

Analysis: Breaking down the relevant material.

Hypothesis: Piling up alternatives by way of ideas.

Incubation: Letting up, to invite illumination.

Synthesis: Putting the pieces together.

Verification: Judging the resultant ideas.

In 1953, Osborn introduced the following, high-level visualization of the creative process—his diamond:

Alex Osborn’s First Visualization of the Creative Process (1953)

Instead of presenting divergent and convergent thinking as two distinct ways of problem-solving as Guilford had, Osborn’s model fuses the two types of thinking into a single, coherent visualization of the creative process. Interestingly, Obsorn uses a vertically oriented diamond shape to convey the direction of the creator’s attention: it flows from the top down. He seems to be implying that the driving force behind creativity is a kind of gravity, or inevitability, like water draining through ground coffee in a cone filter. The process starts with a problem. Ideas then percolate (the more the better), drop into a funnel where they seep through a series of filters, and eventually emerge as a fully blended solution.

Osborn’s initial visualization effectively conveys the relationship between divergence and convergence, but is one-dimensional—it conveys nothing about how the process plays out over time or the iterative nature of creativity.

In the mid-1950s, Osborn began working with the creativity theorist and educator Sid Parnes. Together, they developed the influential “Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Process” (commonly known as CPS). The CPS model and visualization presents a more nuanced and realistic model of the creative process. The diagram below is the “classic” five-stage model (commonly referred to as Version 2.0) that condenses Osborn’s original seven-stage model and simplifies the nomenclature:

The Osborn-Parnes Five-Stage Model of Creative Problem Solving (1967)

From the start, Osborn understood that his problem-solving models and visualizations were idealized representations, and therefore inherently inaccurate. Creativity in practice is messy. When he introduced his original model in 1952, he wrote:

In actual practice, we can follow no such one-two-three sequence. We may start our guessing even while preparing. Our analyses may lead us straight to the solution. After incubation, we may again go digging for facts which, at the start, we did not know we needed. And, of course, we might bring verification to bear on our hypotheses, thus to cull our "wild stabs" and proceed with only the likeliest.

All along the way we must change pace. We push and then coast, and then push. By driving our conscious minds in search of additional facts and hypotheses, we develop a concentration of thought and feeling strong enough to accelerate our automatic pump of association, and make it well up still more ideas. Thus through strenuous effort we indirectly induce "idle" illumination.

—Alex Osborn, Applied Imagination***

Osborn died in 1966, but his work on creative problem-solving was continued by Parnes and his colleagues at the Creative Education Foundation—an organization Osborn established in 1954 to research creative thinking and develop new ways to teach creative problem-solving to students at all levels of education. The Foundation has updated their CPS model four times since the 1960s. Each iteration has incorporated the latest research on learning and problem-solving, and tried to more accurately represent the non-linear, iterative nature of creativity. This is the foundation’s latest visualization, the FourSight model:****

The FourSight CPS Model (also known as the Learner’s Model)

The four stages of the creative problem-solving process in the FourSight model are:

Clarify

Explore the vision: Identify the goal, wish, or challenge.

Gather data: Describe and generate data to enable a clear understanding of the challenge.

Formulate challenges: Sharpen awareness of the challenge and create challenge questions.

Ideate

Explore ideas.

Develop

Formulate solutions: To move from ideas to solutions. Evaluate, strengthen, and select solutions for best “fit.”

Implement

Formulate a plan: Explore acceptance and identify resources and actions that will support implementation of the selected solution(s).

The FourSight model further condenses and clarifies the major stages Osborn identified in 1952. Notice how the language used to describe the various phases of the creative process has evolved. For example, instead of the words “hypothesize” and “incubate,” the model uses the word “ideate”—a familiar term that encompasses both concepts. The way we visualize creativity has also evolved. The four-quadrant diamond identifies the major phases of the creative process—not just divergence and convergence, while the circular arrows that surround it convey both direction and the iterative nature of creative work. The visualization is simple, without being simplistic, and suggestive without being prescriptive.

Other researchers and psychologists have also built on Osborne’s work. The British Design Council’s double diamond model is another attempt to visualize the both the divergent and convergent flow of the creative process, and the iterative nature of creative thinking:

British Design Council Double Diamond Model (2005)

This model has been widely adopted and further developed by the design community. It uses the now familiar diamond shape to convey divergence and convergence, but also tracks the discovery, definition, development, and delivery phases of the creative problem-solving process. The double diamond model also highlights the essential transition between the discover/define phases (the problem space) and the develop/deliver phases (the solution space)—a transition I call “the maker’s threshold.”

The British Design Council has continued to develop its double diamond model. The latest version incorporates the roles keys stakeholders play in the design process. It also highlights the recursive nature of design projects, especially those that have a large contingent of active stakeholders and partners:

British Design Council Double Diamond Model (2019)*****

Models and visualizations of the creative thinking/problem-solving process are not just an academic exercise. They are maps that help us communicate with others about creativity and our creative projects. They are also wayfinding tools that help us reorient ourselves when we’ve lost our sense of direction during our creative work. And, they are learning tools that help us improve our creative thinking, planning, and execution.

The next issue of metaphor will focus on navigating the “maker’s threshold”—the transition between divergence and convergence—and the “make to know” concept of creativity.

Footnotes

* See my article Creativity, Mind-Wandering, Flow, and Deep Play for more mind wandering and the executive function.

** Accounts of life at BBDO in the late 1950s and 1960s inspired the popular Mad Men television series.

*** Applied Imagination is out-of-print, but you can purchase a special reprint edition from the Creative Education Foundation. The Internet Archive has the book in its digital library collection. You may be able to borrow a copy.

**** The FourSight model is based on the work of G.J. Puccio, M. Mance, M.C. Murdock, B. Miller, J. Vehar, R. Firestien, S. Thurber, & D. Nielsen. The FourSight model image is the property of the Creative Education Foundation.

***** The 2005 and 2019 images of The Double Diamond are the property of The British Design Council.

Related Articles

The British Design Council, The Double Diamond: A universally accepted depiction of the design process

The Fountain Institute, What is the Double Diamond Design Process?