TOOLS FOR A PRODUCTIVE CREATIVE LIFE

Subscribe to metaphor—my free newsletter on creative thinking, productivity, and the arts

From the Latest Issue of metaphor

Sprouts: Nurturing and Filtering Ideas in the Age of Generative AI

This post is inspired by a delightful New York Times column by Madison Malone Kircher titled "The Beautiful Chaos of Apple Notes." Picking up on a recent TikTok trend, Kircher asked her readers to share their most "unhinged" Apple notes to themselves . As Kircher points out, "The Notes app occupies an odd perch in the digital landscape. Since its contents aren't usually intended for consumption by anyone else, we are under no pressure to make sense." I began sifting through the flotsam and jetsam of my Apple Notes stream, searching for traces of my own now-unhinged thoughts. However, given my interest in generative AI, I decided to take it a step further and explore what GPT-4 could create from the scraps I discovered, using my reading notes and newsletter articles as its primary data sources. I wondered whether I could use generative AI to rejuvenate these notes and reconnect them to my current network of interests, thoughts, and writing. Here’s result of my experiment and my thoughts on nurturing and filtering ideas in the age of generative AI.

I will begin publishing new issues of metaphor soon. Thank you for your continued interest.

Featured Articles from metaphor

Pattern-seeking has been on my mind, partly because it plays a significant role in generative AI, which I’ve also been thinking and writing about. However, I have been reflecting on the impact of patterns on the creative process for longer than I’ve been thinking and writing about generative AI. This is because patterns are also crucial in the creation and appreciation of art.

At this point, it’s somewhat of a cliche to state that generative AI systems serve as a mirror, reflecting our collective cultural heritage. However, the notion that these systems reveal the ideas, patterns, and biases deeply ingrained in our culture is still apt, particularly if you shift your perspective from thinking of generative AI as a reflection of ourselves in a mirror to a different sensory perception—what we hear, which is most often the voice of others. The auditory experiences of echo, reflection, reverberation, and resonance can help us understand the essential question raised by the brief appearance of the persona Sydney in Microsoft’s early preview of Bing Chat: Who is speaking?

Generative AI is not just a new tool: it’s a new medium. Our interactions with generative AI produce tangible artifacts that express our creative intentions. Like other mediums (oil painting, for example), each generative AI system has its own characteristics that you have to consider as you work with it to express your intentions. And like other expressive mediums, generative AI systems have inherent limitations that you can only overcome with insight and invention—just as the Old Masters had to learn how use vanishing lines, shading, and techniques to create the optical illusions that create a sense of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface.

Generative AI has touched a cultural nerve. Every day there’s a fresh wave of stories, articles, and opinion pieces on the latest advances in generative AI. The frenzy over generative AI will fade, as all stories do in our headline driven news environment, but generative AI is here to stay. We don’t know its full potential, its limitations, or the real dangers it poses. What we do know is that thoughtful discussion and debate on these important topics requires a shared understanding of the technologies themselves. This article is focused on text generation tools, including GPT-3 and ChatGPT.

Generative AI is a type of artificial intelligence that’s capable of analyzing vast amounts of data (text, images, music, video, code, and more) to produce new, unique content. What makes generative AI special is the last part of the sentence above—generative AI systems use existing data to produce unique and creative output that hasn’t been seen before. This article will help you get started with generative text-to-image tools like DALL·E, Stable Diffusion, and Midjourney.

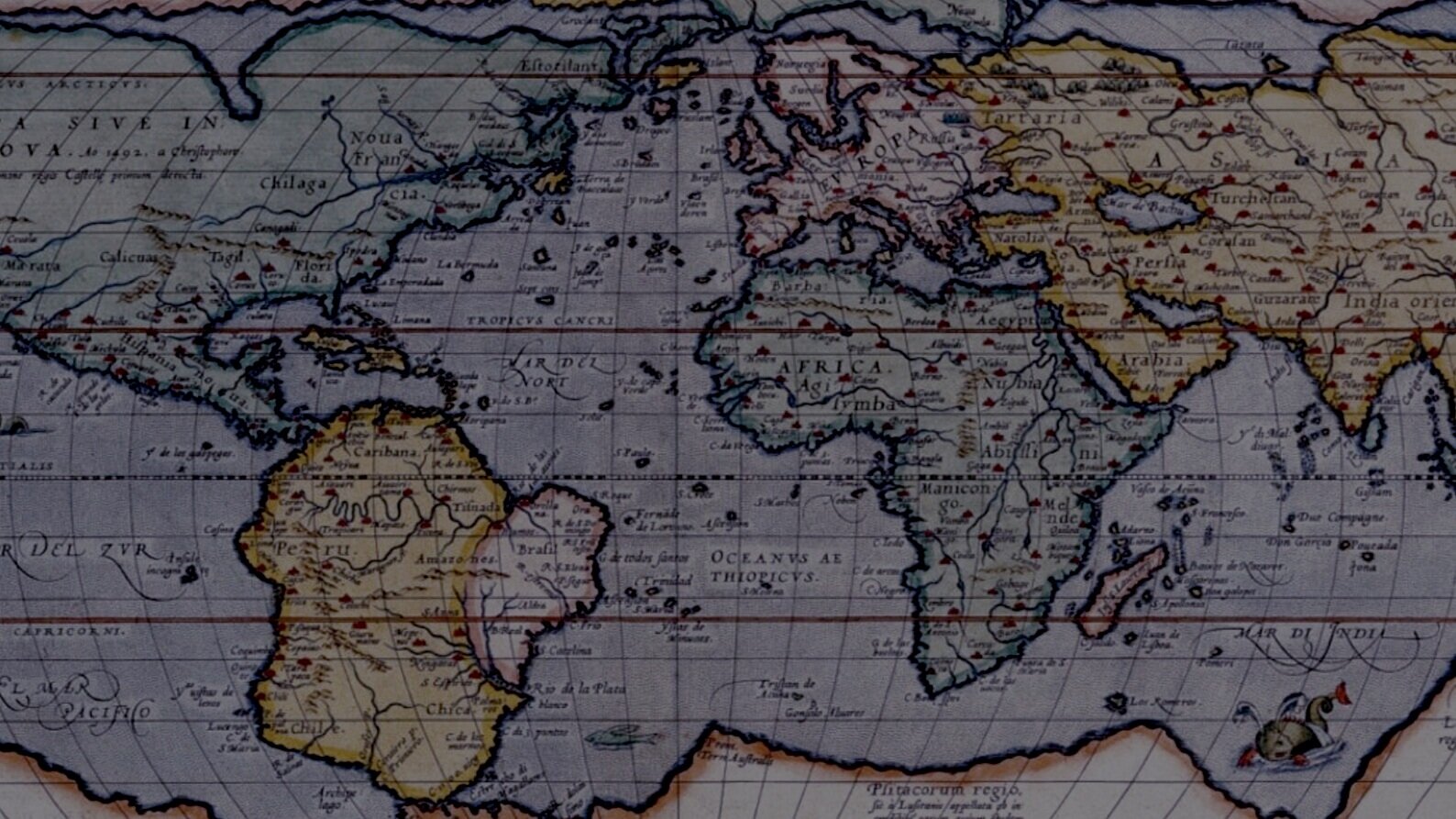

How do you see the world? The literal answer is that you see through your two eyes. But it's not that simple. The pictures of the world you carry in your head are fabrications assembled from what you see with your unaided vision and what you see through the myriad lenses that alter what you see with your naked eyes. Generative AI, and especially generative image creation tools, are something new. But the connection between image making and technology is not new. In fact, it’s older than we’ve previously believed.

Learning how to think with images begins with learning how to see, or perhaps more accurately, learning how to un-see. Your open eyes are always looking, collecting images and sending them to your brain. And your brain is always processing the images it receives—comparing new images to what you already know and creating connections between different sets of related images and ideas. But most of us rarely stop to think about how we gather, sort, categorize, and group the visual elements that make up the images we’re constantly assembling in our brain.

Digital content is becoming more and more like thought itself. It exists in a space that is both real and not real, fluid and ever-changing, both ephemeral and permanent. We increasingly interact with our content using tools designed to capture and manipulate our thoughts, but the thoughts themselves are not always fully formed or logical. In other words, we are now thinking with digital information in the same way we think with the thoughts we store in our head.

It’s not an overstatement to say that our attention is under siege and we are losing—losing our ability to focus. Our struggle to focus is both a personal and a cultural problem. Individual and legislative action can mitigate it, but taking action requires a cultural change—one that begins with the development of a more nuanced understanding of attention itself. Once we better understand the nature of attention, we can decide how and when we want to share it and protect it.

This is the 50th article from my newsletter metaphor. When I launched the newsletter in October 2020, I used the tagline “Tools for a productive creative life.” I didn’t know where my initial intention would take me—and that’s been the fun of it! This article presents five essential things I’ve learned about creativity from writing the last 49 issues: over 85,000 words. More to come soon…

When we think about revision, we usually think about reworking the way we are expressing our ideas: restructuring our thoughts and refining the words we’re using to express them. But there’s a type of revision that comes earlier in creative problem-solving. It’s focused on shifting the approach you’re taking during the formative stages of ideation: revision as the art of seeing from a different perspective, with a fresh mind.

In my last article I explored how the way we visualize the creative problem-solving process has evolved over the last 70 years. The familiar Divergence/Convergence kite model eventually developed into the popular double diamond model that’s still taught in design schools. The FourSight model, a more recent visualization, is popular in education, especially in primary and secondary school settings. Each of these models conveys useful insights into the creative problem-solving process. In this article I introduce you to a new way of visualizing the creative problem-solving process I’ve developed. My Make-to-Know model revolves around a a concept I call “The Maker’s Workshop”—the generative space where your ideas collide, spark, and sometimes fuse. It’s the heart of the creative problem solving process.

The psychologist Robert Sternberg, a leading researcher and author on creativity, first introduced the Propulsion Theory of Creative Contributions in 19991. The theory describes eight ways a creative contribution such as a research paper, artwork, movie, television show, book, product, or innovative idea can move (propel) a field of endeavor in a particular direction. Sternberg’s theory adds another important dimension to our understanding of creativity: context. The purpose of a creative contribution matters.

Who are your creative icons? Chances are most of the artists, scientists, inventors, and others who come to mind are widely celebrated “geniuses”—the household names of creativity. Creative achievements of world-changing magnitude are rare. Still, this is the highwater mark many of us use to measure our own creativity. If the gauge you’re using to assess your creativity includes just one level marked “genius,” you’re setting yourself up for failure. We need a more nuanced understanding of creativity.

We’ve all become more familiar (and hopefully adept) at calculating risk over the past two years as we’ve struggled to balance the demands of daily life with the threats posed by the seemingly endless waves of the COVID-19 virus. We’ve always lived with risks, but the pandemic has significantly altered the risk/reward ratio of everyday life. It’s also made many of us more risk averse. Our COVID-induced diminished tolerance for risk-taking may also have another significant consequence: you may be feeling an unfamiliar sense of alienation from your creative confidence and desire to engage in new creative work. You’re not alone, and you can rebuild your confidence and rekindle your passion for creative work, if you’re willing to take a few small risks.

Our modern concept of creativity is deeply rooted in the value system of the artists and intellectuals of the Romantic era who believed that the greatest sin was being derivative. The biases of the Romantics still influence us. Our culture prizes originality and individuality; we celebrate the “pioneers” and “trailblazers. But our obsession with originality blinds us to the value of thinking with others and untapped knowledge in our collective intelligence.

In his essay “Communicating with Slip Boxes,” Niklas Luhmann argues that his collection of notes is not a passive archive of his thoughts, but a “competent” conversation partner capable of surprise. Luhmann isn’t a mad scientist imbuing his inanimate creation with human qualities, he’s stating a fact. The organization of his note-taking system allowed him to pose a question, then follow his branching and linked thoughts to unexpected answers. The “conversation” is the result of an open, loosely organized system designed to surprise.

This introduction to Niklas Luhmann’s ideas on note-taking and organizing notes is designed to help you to develop your own thinking about how you use notes and develop ideas in your note-taking system. We need to build a vocabulary for discussing notes, note-taking, and working with notes so we can more effectively implement our ideas in the applications and systems we use. Luhmann’s Zettelkasten methodology is a good starting point.

Most of us don’t spend much time thinking about notes and note-taking—and why would you? Most notes we take are disposable: quick scratches meant to jog our memory. But notes serve a wide variety of purposes. Reminding is only one of them. Learning to distinguish between the types of notes you take and how to use your notes effectively is an essential part of thinking outside the brain.

This article introduces a new series on creativity and the extended mind: how we use tools, our body, and the world around us to enhance the capacity of our brain and create in ways the mind can’t manage on its own. In this series I’ll be writing about note-taking, personal knowledge management systems, thinking with your body, and more.

Self-directed creative work is different from other forms of creative work. Typically, there’s not a list of specifications you can check off on your way to “done.” Success in creative endeavors can only be measured by the recognition that the work is “good,” that it satisfies the creator’s intention—your intention. “Good” is not the same as “perfect” or “finished,” in the sense that all possible improvements have been explored and closed, but “good” is sufficient. How do you know when your work is good? You use your aesthetic: the collection of formal, material, intellectual, functional, emotional, and spiritual qualities that please you.

I’m a perfectionist. Perhaps you are too… Most of us think of perfectionism as a personal failing—a toxic combination of overly high personal standards and unrelenting self-judgement. But perfectionism is deeply ingrained in our culture. It’s time to reframe the idea of perfection and develop a new relationship with perfectionism.

We’re all familiar with the inner critic: the voice inside your head that delights in belittling, criticizing, and judging you. This article is focused on reconnecting with the protective impulse the inner critic is expressing, and using that impulse as a catalyst for developing your creativity.

It feels out of step with the times to write an article on beauty, but it’s what beauty demands. What is the purpose and nature of beautiful things? This article collects some of my thoughts on these questions.

Keep your creative fire burning! Subscribe to metaphor

Thank you!

You will receive a confirmation email momentarily.

Please click the button labeled ”Confirm your email” to confirm your subscription.