Thinking with Others

This is the sixth and final installment in my series on thinking outside the brain. Up to this point in the series, I’ve focused on ways of enhancing the cognitive capacity and functioning of the brain in solitude—disconnected from the examples, guidance, expertise, and support of others. But as Annie Murphy Paul notes in The Extended Mind:

... the development of intelligent thinking is fundamentally a social process. We can engage in thinking on our own, of course, and at times solitary cognition is what’s called for by a particular problem or project. Even then, solo thinking is rooted in our lifelong experience of social interaction; linguists and cognitive scientists theorize that the constant patter we carry on in our heads is a kind of internalized conversation. Our brains evolved to think with people: to teach them, to argue with them, to exchange stories with them. Human thought is exquisitely sensitive to context, and one of the most powerful contexts of all is the presence of other people. As a consequence, when we think socially, we think differently—and often better—than when we think non-socially.

Our modern concept of creativity is deeply rooted in the value system of the artists and intellectuals of the Romantic era. Many of the most well known artists of the movement are still familiar to us:

Poets, novelists, and writers such as William Blake, Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Keats, Edgar Allan Poe, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman.

Painters such as John Constable, Eugène Delacroix, Theodore Gericault, Francisco Goya, and J. M. W. Turner.

Composers such as Johannes Brahms, Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt, Giacomo Puccini, Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Franz Schubert, and Giuseppe Verdi.

For artists and thinkers of the Romantic era, the greatest sin was being derivative. They rejected the models and rules of the past, and instead drew inspiration from their imagination and emotions. The German poet Friedrich Schlegel, the first to use the term “romantic” in relation to literature, defined it as “literature depicting emotional matter in an imaginative form.” Imagination, emotion, spontaneity, subjectivity, individuality, and originality are all characteristics of Romanticism.

The biases of the Romantics still influence us. Our culture prizes originality and individuality; we celebrate the “pioneers” and “trailblazers.” Even the way we define creativity (“The use of the imagination or original ideas, especially in the production of an artistic work,” from the Oxford Dictionary) reflects the ideals of the Romantics. Romanticism has been liberating and empowering, but there’s also a shadow side to this inheritance. The British philosopher Isaiah Berlin believed Romanticism disrupted the Western traditions of rationality, moral absolutes, and agreed values which led to “something like the melting away of objective truth” (as quoted in English Literature in the 19th Century). Berlin’s apprehension has become our reality.

And yet, as Paul notes, to some degree our “wariness” of “group-think” may be justified:

Uncritical group thinking can lead to foolish and even disastrous decisions. But the limitations of excessive “cognitive individualism” are becoming increasingly clear as well. Individual cognition is simply not sufficient to meet the challenges of a world in which information is so abundant, expertise is so specialized, and issues are so complex. In this milieu, a single mind laboring on its own is at a distinct disadvantage in solving problems or generating new ideas. Something beyond solo thinking is required—the generation of a state that is entirely natural to us as a species, and yet one that has come to seem quite strange and exotic: the group mind.

—Annie Murphy Paul, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain

In her book, Paul introduces three types of thinking with others: thinking with experts, thinking with peers, and thinking in groups.

Thinking with Experts

Paul’s concept of “thinking with experts” revives one of the essential elements of ancient Greek and Roman schools: emulating the masters. Imitation was a cornerstone of classical education but has largely fallen out of favor in contemporary pedagogies.

The conventional approach to cognition has persuaded us that the only route to more intelligent thinking lies in cultivating our own brain. Imitating the thought of other individuals courts accusations of being derivative, or even of being a plagiarist—a charge that can end a writer’s career or a student’s tenure at school. But this was not always the case. Greek and Roman thinkers revered imitation as an art in its own right, one that was to be energetically pursued.

—Annie Murphy Paul, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain

Our obsession with original thinking blinds us to the true value of imitation: conscious imitation is the fast-track to innovation. Paul points out that imitation has five distinct advantages:

Imitators can use other people as filters. They can leverage the experience and knowledge of those with proven pathways to success.

Imitators can choose from a wide variety of solutions, instead of investing and committing to just one. This makes them more responsive to the demands and opportunities of the moment.

Imitators can avoid costly mistakes by learning from those who went before them.

Imitators can avoid being misled by bad information from competitors or the market. Because copiers begin with what others have already done or produced, they begin with a clear understanding of the strategies and products others have already analyzed and refined.

Imitation is cost effective. As Paul notes, “Imitators save time, effort, and resources that would otherwise be invested in originating their own solutions. Research shows that the imitator’s costs are typically 60 to 75 percent of those borne by the innovator—and yet it is the imitator who consistently captures the lion’s share of financial returns.”

Our disapproval of imitation as a strategy is heavily influenced by our consumer culture. Cheap “knock-offs” of high value goods (especially fashion products) regularly flood the market. While imitation is a form of flattery, counterfeit products infringe on intellectual property rights, diminish the likelihood of investment in the countries that manufacture the goods, reduce legitimate tax revenues, and are often produced in factories that fail to meet environmental standards and child labor laws. But rote copying isn’t what Paul is promoting. We need to separate our understandable reaction to counterfeit goods with imitation as a pathway to creativity.

… imitation (if we can get past our aversion to it) opens up possibilities far beyond those that dwell inside our own heads. Engaging in effective imitation is like being able to think with other people’s brains—like getting a direct download of others’ knowledge and experience. But contrary to its reputation as a lazy cop-out, imitating well is not easy. It rarely entails automatic or mindless duplication. Rather, it requires cracking a sophisticated code—solving what social scientists call the “correspondence problem,” or the challenge of adapting an imitated solution to the particulars of a new situation. Tackling the correspondence problem involves breaking down an observed solution into its constituent parts, and then reassembling those parts in a different way; it demands a willingness to look past superficial features to the deeper reason why the original solution succeeded, and an ability to apply that underlying principle in a novel setting. It’s paradoxical but true: imitating well demands a considerable degree of creativity.

—Annie Murphy Paul, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain

Oded Shenkar, a professor of management and human resources at Ohio State University cited by Paul, says that tackling the correspondence problem involves three steps:

Specify your problem and identify an analogous problem that has been solved successfully.

Rigorously analyze why the solution is successful.

Identify how your circumstances differ from the analogous problem, then figure out how to adapt the original solution to the new setting.

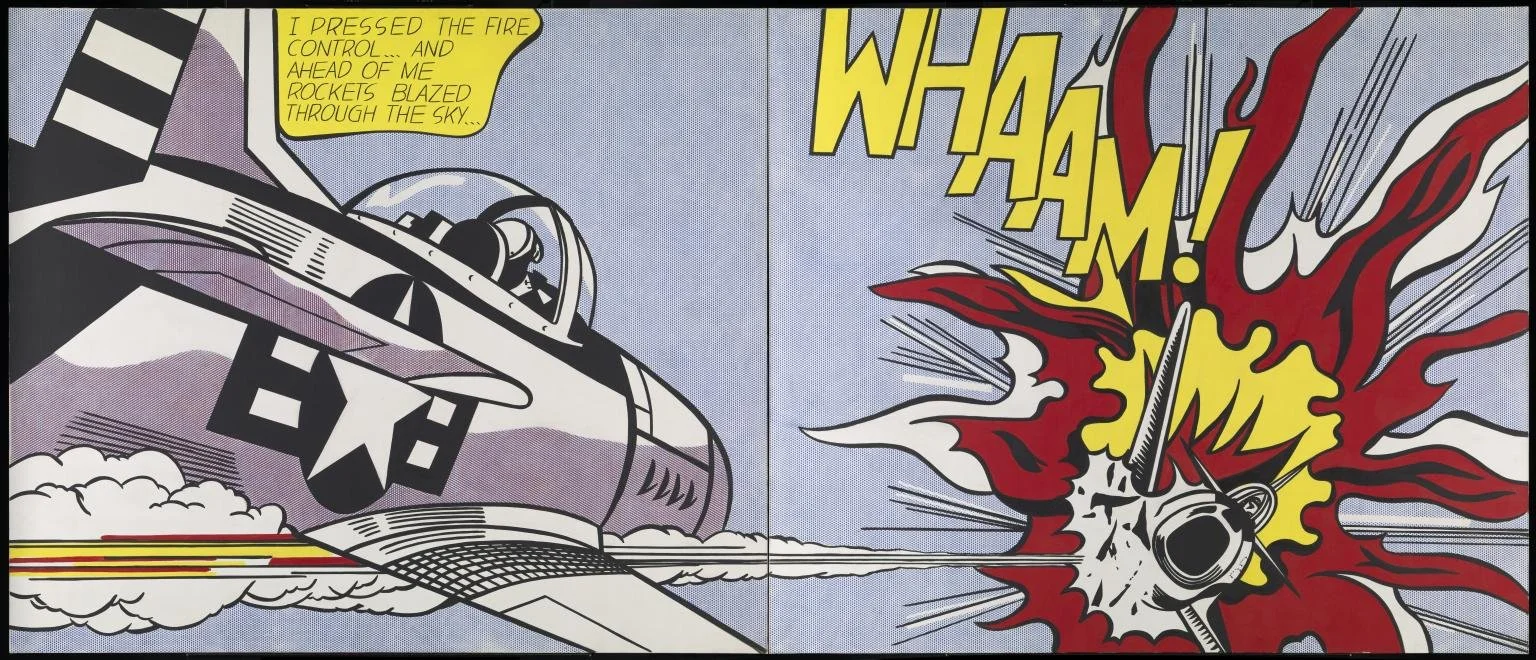

Let’s look at an example of how imitation and the challenges of adapting an imitated solution were addressed in a creative context. The artist Roy Lichtenstein was one of the most influential and successful artists in the pop art movement of the 1960s. Lichtenstein adopted the content, style, and production values of comic books to produce large-scale paintings that echoed the grand European history paintings—traditionally regarded as the highest form of Western art.

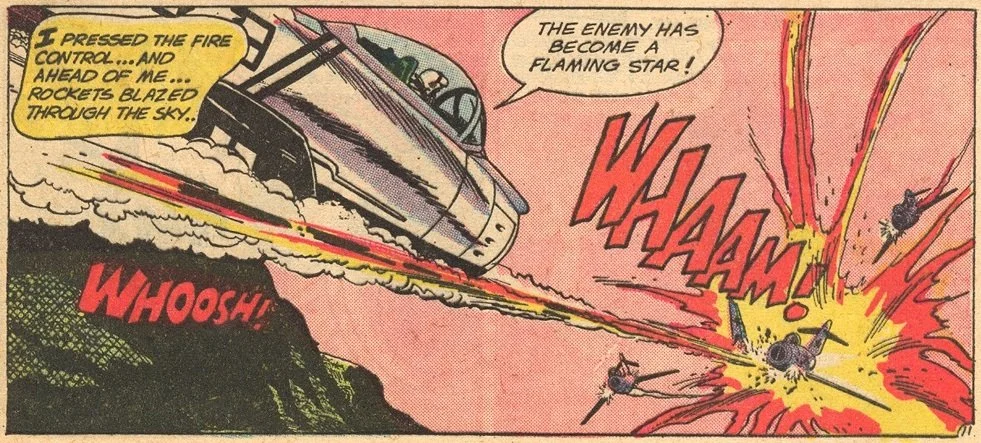

Painted in 1963, Lichtenstein’sWhaam! Is widely regarded as one of the best examples of pop art. The primary source for the painting is a comic book frame by the illustrator Irv Novick, a friend Lichtenstein met at the army boot camp where he and Novick trained during the Second World War.

Comic book frame illustrated by Irv Novick in the 1962 DC comic All-American Men of War

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Lichtenstein picks up elements of the original, including some of the formal traditions of machine-printed comics, such as the use of thick black lines to enclose areas of primary color, the lettering style, and the uniform areas of Ben-Day dots. But there are also significant differences: the image is simplified both in its content and style, and it’s more balanced and unified. Lichtenstein also reworked the lettering of the word “Whaam!” and the fireball so your eye now moves from the thought bubble to the wording of the sound effect, to the explosion itself. He also dramatically increased the scale of the image, from a few inches to over 5 feet high and over 6 feet wide.

Lichtenstein transformed a fleeting moment in a generic war story into a vivid commentary on America’s obsession with military power and its growing involvement in the Vietnam War. (Links to three interesting commentaries on the painting follow below.) In the right hands, imitation is a pathway to inspiration.

Thinking with Peers

The second type of thinking with others that Paul focuses on is “thinking with peers.” Unlike imitation, which begins as a form of deference, thinking with peers is inherently interactive. It engages our emotions as we express ourselves, persuade, and argue. “We are wired to be social,” says the psychologist Matthew D. Lieberman in his book Social: Why Our Brains are Wired to Connect. In fact, social connections play such a significant role in our well-being that we have three different “social networking” systems in our brains, each with different strengths:

The first network is focused on connection, on feeling and intuiting social pains and pleasures—our own feelings and the feelings of others. The connection network links our well-being to our feelings of social connectedness.

The second network is focused on mind-reading, on understanding and anticipating the actions and thoughts of those around us. This network enhances our ability to connect and successfully interact with others.

The third network is focused on harmonizing, on balancing our sense of self with the beliefs and values of those around us. Successful harmonizing leads to the sense of belonging, which is essential to our well-being as well as the development and evolution of the group.

Lieberman adds:

While we tend to think it is our capacity for abstract reasoning that is responsible for Homo sapiens’ dominating the planet, there is increasing evidence that our dominance as a species may be attributable to our ability to think socially. The greatest ideas almost always require teamwork to bring them to fruition; social reasoning is what allows us to build and maintain the social relationships and infrastructure needed for teams to thrive.

There are some things that we do better in groups, including learning. A 2019 study on the trajectories of PhD students’ research skill acquisition found that the development of their essential research skills was more closely related to their interaction with other students than with faculty mentors. PhD students were four to five times more likely to demonstrate positive skill acquisition when they were active participants in laboratory discussions with other senior graduate students and postdocs. Actively learning with a group of peers is inherently social. It elicits levels of sharing, debating, mentoring, and camaraderie that don’t come naturally in traditional one-to-many faculty led settings. It turns out that one of the key differences is related to the importance of conversation. When we converse with others (as opposed to just listening), specialized brain functions are engaged that anticipate the words our conversation partner will use and how we will respond. This added level of engagement helps us learn and retain more than we do when we are just listening.

There’s a tension between our desire to maintain intellectual independence and our need to connect with the group mind. We now know that the neural systems that support these two functions are actually separate networks. Lieberman again:

The surprising thing is that even though social reasoning feels like other kinds of reasoning, the neural systems that handle social and nonsocial reasoning are quite distinct, and literally operate at odds with each other much of the time. In many situations, the more you turn on the brain network for nonsocial reasoning, the more you turn off the brain network for social reasoning. This antagonism between social and nonsocial thinking is really important because the more someone is focused on a problem, the more that person might be likely to alienate others around him or her who could help solve the problem. Effective nonsocial problem solving may interfere with the neural circuitry that promotes effective thinking about the group’s needs.

Humans are storytellers. We tell stories to interpret the past and shape the future, to reason and persuade, to manage conflicts, and to express our feelings. Annie Murphy Paul tells us that stories are “‘psychologically privileged,’ meaning that they are granted special treatment by our brains.” We listen to stories more closely, understand them better, and remember them more accurately—up to 50 percent more accurately than information conveyed in expository prose.

Stories play to our brain’s tendency to seek causal relationships. But well-told stories don’t connect all the dots… They leave room for us to infer cause and effect. Those gaps make us think about the story, and ultimately make it more likely that we’ll remember the story. Brain-scanning studies show that when we listen to a story, our brains experience the action as if it were happening to us. We run a simulation of the story in our mind and in the process gather the details in the story that help us understand the interpersonal dynamics in play. Listening to stories also helps us learn and remember the steps the protagonists in the story take to accomplish their goals. Stories forge connections: they are an effective way of transferring both stated and implied knowledge.

Stories serve one other important function: they help us resolve the tension between our desire for intellectual independence and the needs of the group. In his book The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, Jonathan Gottschall shares what he calls the “master formula for storytelling”: Story = Character + Predicament + Attempted Extrication. The storytelling formula is an algorithm for creating social connections between the needs of the individual and the needs of the group. The stories we tell express our individuality: we are the main character, our predicaments and our attempts to extricate ourselves are the main focus. The collected stories told by others help us understand and develop empathy for the predicaments of the group, and over time, develop the shared sense of values and approaches to resolving predicaments that add up to a culture. We shape our stories and stories shape us.

Thinking with Groups

Thinking in groups (aka “groupthink”) has a bad reputation. Thankfully, it’s being rebranded! “Socially distributed cognition” is the term psychologists are now using to refer to thinking with the minds of others. The serious and complex existential problems we need to address demand the attention of our collective intelligence. Paul frames both the challenge and the opportunity:

Knowledge is more abundant; expertise is more specialized; problems are more complex. The activation of the group mind—in which factual knowledge, skilled expertise, and mental effort are distributed across multiple individuals—is the only adequate response to these developments. As group thinking has become more imperative, interest has grown in learning how to do it well. At the same time, reimagined theories and novel investigative methods have granted researchers new insight into how the group mind actually operates, placing the field on a genuinely scientific footing. Neither senseless nor supernatural, group thinking is a sophisticated human ability based on a few fundamental mechanisms.

—Annie Murphy Paul, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain

To harness the power of our collective intelligence, we have to first understand how group thinking differs from individual thinking. “When we think on our own,” Paul writes, “all of our thoughts get a hearing. But when we think as part of a team, it takes intentional effort to ensure that everyone speaks up and that everyone shares what they know.” As we learned in the section above on thinking with peers, listening, questioning, and discussing amplify the quantity and quality of the information we take in and retain.

Paul also points out that when we are thinking with a group, “we need to make our thought processes visible to others.” The notes, drawings, presentations, and other documents we create to share our ideas with others are usually more explicit than the notes we create for ourselves, meaning that the group is working with more fully developed ideas.

The third advantage of working in a group is that we are able to tap into a wider range of knowledge and skills, as well as deeper levels of specific expertise, than we—on our own—can muster.

The benefits of harnessing the power of collective intelligence are increasingly clear:

The shift is easiest to see—and to measure—in the social and physical sciences, where contributions by single individuals were once the norm. Today, fewer than 10 percent of journal articles in science and technology are authored by just one person. An analysis of book chapters and journal articles written across the social sciences likewise found “a sharp decline in single-author publishing.” In economics, solo-authored articles once predominated; now they account for only about 25 percent of publications in the discipline. In the legal field, a 2014 survey of law reviews concluded that nowadays, “team authors dominate solo authors in the production of legal knowledge.” Even the familiar archetype of the solo inventor (think Thomas Edison or Alexander Graham Bell) is no longer representative. A 2011 report found that over the previous forty years, the number of individuals listed on each US patent application had steadily increased; nearly 70 percent of applications now named multiple inventors.

—Annie Murphy Paul, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain

So how do we shift from an individual focus to a group focus? Through the conscious development of “synchrony.” Paul says, “A substantial body of research shows that behavioral synchrony—coordinating our actions, including our physical movements, so that they are like the actions of others—primes us for what we might call cognitive synchrony: multiple people thinking together efficiently and effectively.”

Synchrony signals others that we are open to and capable of cooperation. Interestingly, one of the primary ways to develop synchrony is through synchronous movement: for example, bowing and kneeling together in prayer, marching together, exercising together, and dancing together. Moving together synchronously heightens our awareness of being part of a group, builds a shared sense of confidence that the group will be productive, and sensitizes us to the presence of others.

There are other ways to synchronize groups, including:

Shared physical or emotional arousal

Shared attention on an object or information

Shared motivation on a goal

Shared training

Shared rituals, such as eating lunch together

Shared incentives, such as a sense of a shared fate

Synchrony changes the way we think and feel about working in groups:

On an emotional level, synchrony has the effect of making others, even strangers, seem a bit like friends and family. We feel more warmly toward those with whom we have experienced synchrony; we’re more willing to help them out, and to make sacrifices on their behalf. We may experience a blurring of the boundaries between ourselves and others—but rather than feeling that our individual selves have shrunk, we feel personally enlarged and empowered, as if all the resources of the group are “now at our disposal.

—Annie Murphy Paul, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain

We are learning how to design and sustain working groups that balance our need for autonomy with the active participation required to establish and maintain a productive group identity. It’s no exaggeration to say that our future depends on our ability to work in groups.

In Closing…

This article concludes my series on thinking outside the brain—but it’s not really an ending, it’s just a pause… Creative thought begets creative expression. Producing creative work requires us to think outside the brain as we translate our creative ideas into their tangible form. What’s changing is that people in all walks of life are also beginning to consciously think outside their brains. Thinking beyond the brain—thinking with the body, with movement, with our natural spaces and thoughtfully designed constructed spaces, thinking with others (experts, peers, and groups) doesn’t just enhance our intelligence, it gives us the opportunity to reframe the very idea of intelligence…

In her conclusion to her book, Annie Murphy Paul describes the “transactional” nature of our intelligence as “a fluid interaction between our brains, our bodies, our spaces, and our relationships.” She adds, “The capacity to think intelligently emerges from the skillful orchestration of these internal and external elements.” We are not born with a fixed level of intelligence—our intelligence ebbs and flows, based on the situation, the relevant knowledge we have in our heads, and our ability to tap into the applicable knowledge in our extended mind. In a world of increasingly complex problems, our growing awareness of the power of the extended mind should give us hope.

Additional Reading on Roy Lichtenstein's Whaam!

“Is Lichtenstein a Great Modern Artist Or a Copy Cat?” BBC website

“Roy Lichtenstein: Whaam!” The Tate Gallery website

Jeremy Briggs, “Whaam! The Aeronautical Perspective,” Down the Tubes website