The Elusive Definition of Creativity

Who are your creative icons? Chances are most of the artists, scientists, inventors, and others who come to mind are widely celebrated “geniuses”—the household names of creativity, such as Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Louis Armstrong, Pablo Picasso, Thomas Edison, Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, Toni Morrison, and Steve Jobs to name just a few of modern history’s most eminent creators. We rightfully celebrate these geniuses because their conceptual breakthroughs and creative works have permanently changed the world we live in.

Creative achievements of world-changing magnitude are rare. Still, this is the highwater mark many of us use to measure our own creativity. If the gauge you’re using to assess your creativity includes just one level marked “genius,” you’re setting yourself up for failure. We need a more nuanced understanding of creativity—an approach to thinking and talking about creativity that isn’t binary: either you’re a creative genius or you’re not. We also need a way of contextualizing our creative work so we can more clearly understand motivations and intentions that drive our creativity at each stage of our development, and how we can be more empathetic judges of our own work.

Creativity Is Hard to Define

We’re sloshing around in articles, podcasts, and books about the creator economy, the creative class, creativity in education and in business. But an objective definition of creativity eludes us. Why? Because the creative process, how creativity manifests itself, and what constitutes creativity differs from context to context.

The serious study of creativity began in the 1950s and accelerated in the 1960s, in part due to Russia’s launch of the Sputnik satellite, which triggered the space race. The conformity of the 1950s gave way to the self-proclaimed “creative revolution” of the 1960s. Suddenly, the use of the word “creativity” skyrocketed. The chart below tracks how frequently the word “creativity” appears in Google’s massive corpus of digitized books, starting in the year 1800. It didn’t even register a blip until 1920, roughly forty years after the birth of the field of psychology:

Frequency of the word “creativity” in the Google Books corpus (1800 - 2019)

But look at what happened in the 1950s—the use of the word “creativity” took off, as our culture turned toward understanding and exploiting our ability to use our imagination to discover new ideas, possibilities, connections, and solutions to increasingly complex problems, including rocketing a man into space.

The Four C Model of Creativity

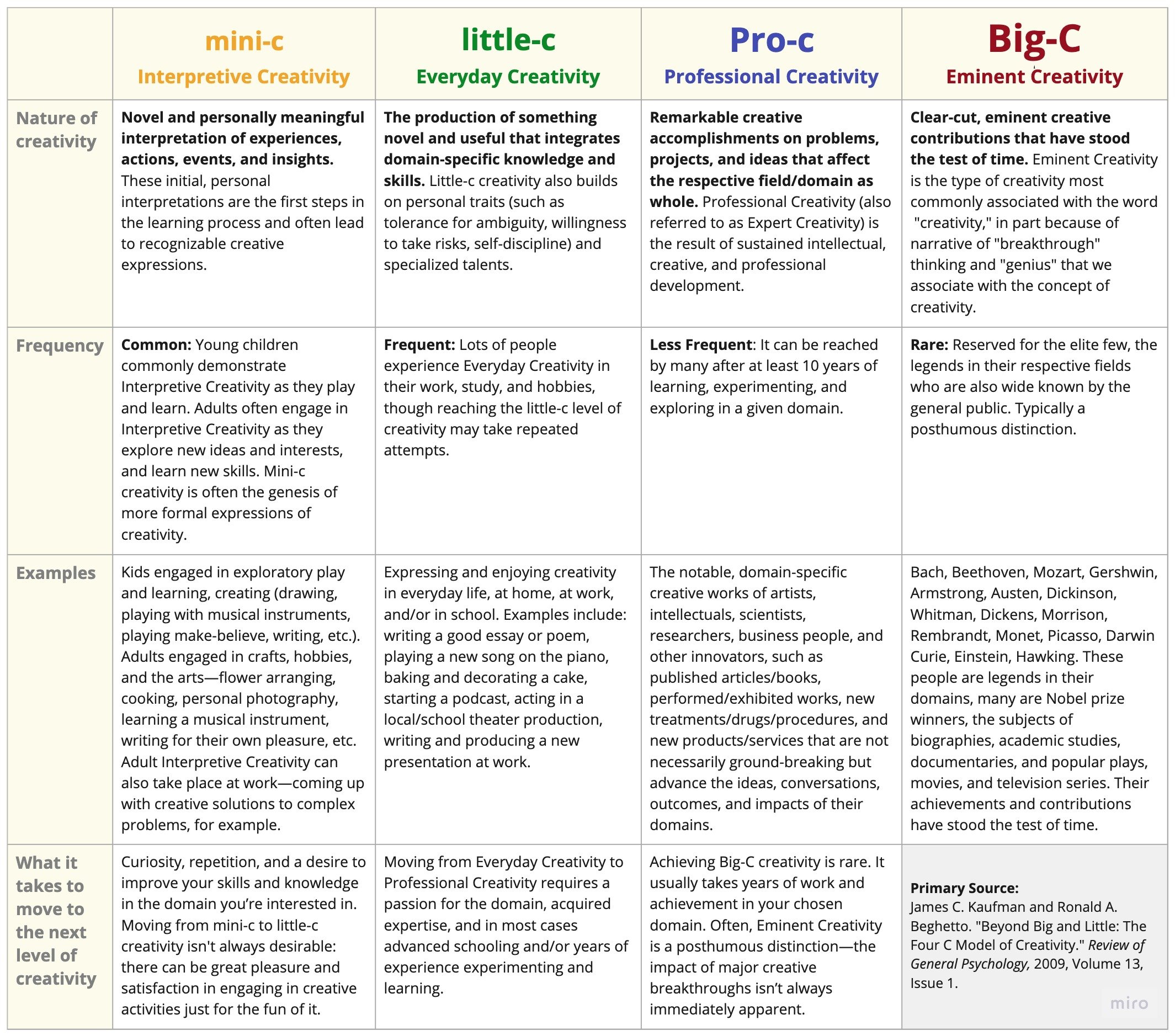

In 2009, the psychologists James C. Kaufman and Ronald A. Beghetto published their influential article “Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity.” Their model clarifies what creativity is in its earliest stages, where it supports the development of personal curiosity, exploration, and learning, to creativity in its most impactful forms in our professional lives. Their model builds on the pioneering work on creativity and flow of the late Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who identified two types of creativity: “little-c” creativity (Everyday Creativity) and “Big-C” creativity (Eminent Creativity). The Big-C/little-c model lays out useful endpoints that clearly distinguish the nature of the significant contributions made by the most highly regarded achievers in a given field from the smaller, incremental achievements made by “ordinary” people.

The problem with Csikszentmihaly’s model is that everything except breakthrough creativity is designated as everyday creativity. A writer whose first stories are appearing in a magazine falls into the same category of creative achievement as the late Joan Didion, a writer whose talent and work was celebrated in her lifetime, but who hasn’t yet achieved legendary status. (This is not a comment on the quality of Didion’s work—one requirement of achieving legendary status is that the value of your work has stood the test of time. It’s too early to know how future generations will view her work.)

Kaufman and Beghetto solve this problem by adding two new types of creativity to Csikszentmihaly’s model: “mini-c” creativity (Interpretive Creativity) and “Pro-c” creativity (Professional Creativity). Their additions create meaningful differentiation in the overly broad category of Everyday Creativity. They also clarify the route and the waypoints between our earliest creative endeavors and the achievement of Big-C status.

Note: I have kept Csikszentmihaly, Kaufman, and Behgetto’s intentional use of lowercase and uppercase letters in the four category names.

The table below provides more information on The Four C Model of Creativity, including examples and the requirements for progressing from one category to the next.

The Four C Model of Creativity

View and download a PDF version of The Four C Model of Creativity table.

Too many creatives are under the spell of the narrative of genius, believing that achieving legendary status (in their lifetimes, no less) is the only worthwhile validation of their creativity. It’s difficult to think otherwise in our celebrity focused culture.

The Four C model validates other, more achievable and equally worthy manifestations of creativity. It has important implications for how we think about the role creativity plays in our lives, how we judge our creative work and careers, and perhaps most importantly, the story we tell ourselves about the value of our creativity.

mini-c creativity is essential to developing your curiosity, learning, and discovering what may eventually become creative passions, especially for children. The mini-c concept also validates the decision many of us make to remain dedicated amateurs in some areas of our creative lives. One of the primary satisfactions in personal creative pursuits is that you’re creating for an audience of one. You are the only judge of the worth of your work. Mini-c creativity is the playground for your creative intuitions and for many, the gateway to a creative life.

little-c creativity evolves as you follow your creative passion and focus your time and attention on a specific domain. Creativity at this level involves learning about the history, customs, and quality standards of your chosen domain. If you’re building toward a career in your chosen field, you’ll also need to learn what it takes, both personally and professionally, to develop your domain expertise and command of the required skills. In addition, you need to learn how to solicit feedback on your work and respond to it with appropriate consideration.

Pro-c creativity requires a sustained passion for your field along with continuous investment in your professional development. It’s achieved after years of research, experimentation, and creative expression in your specific domain or field. Pro-c creators are experts who regularly meet and often exceed the standards of their professions. Participation in the Pro-c level also exposes you and your work to the highest levels of scrutiny from other experts in your field, and often from the public.

Kaufman and Beghetto’s addition of the Pro-c level of creativity addresses the problem I noted above where a beginning writer is judged by the same standards as an accomplished writer. As they note in their article, Pro-c creativity doesn’t always equate to financial reward—some fields don’t reward even their most accomplished contributors with a living wage. But Pro-c creativity has other rewards: contributors at this level often produce work that changes the direction of their field. Some even influence society as a whole. An even smaller number may eventually be recognized as a “genius.”

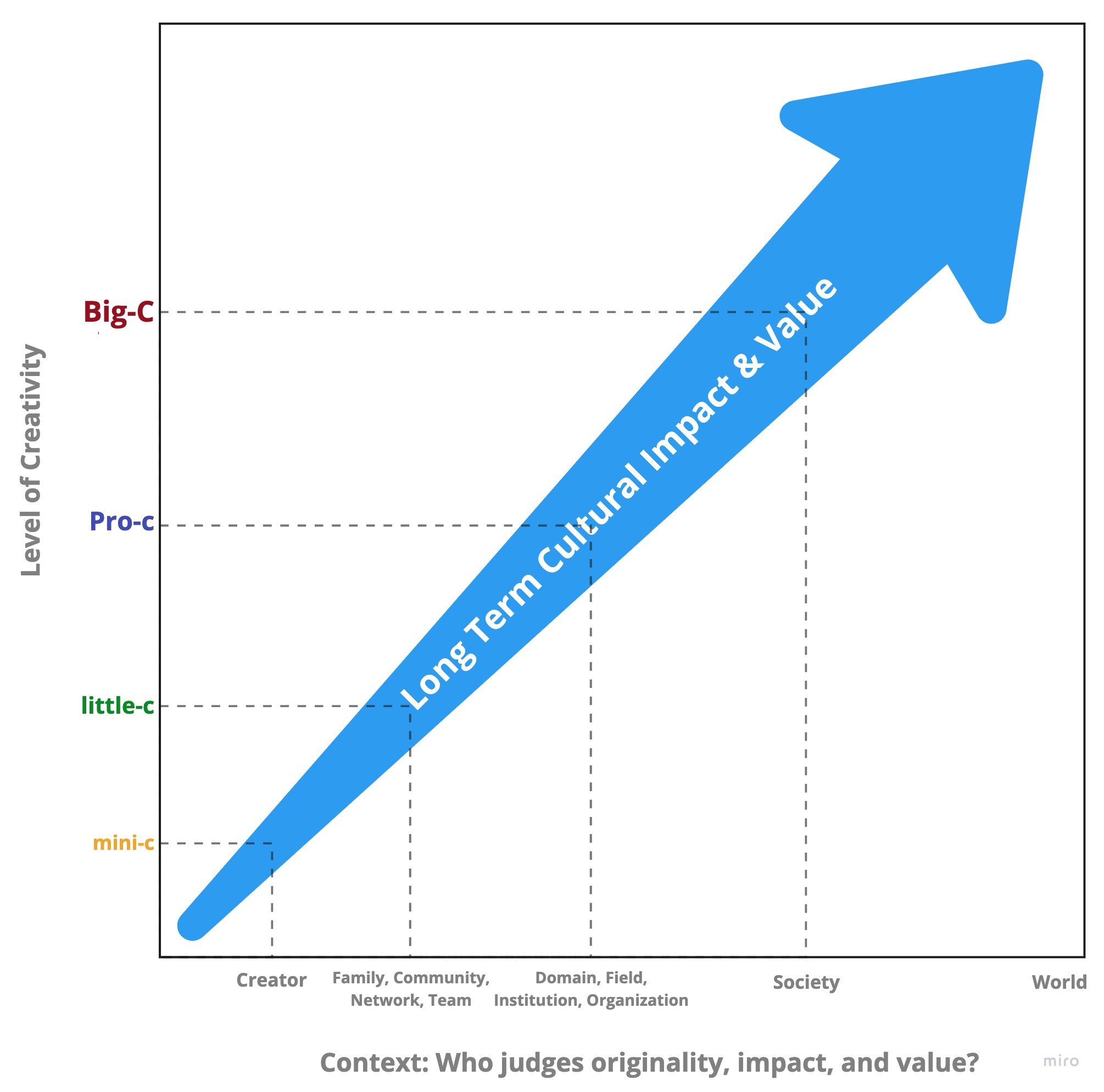

Creativity and Context

You can use the Four C Model to assess where you are in your creative career, set level-appropriate goals for yourself, and clarify what it will take to advance to the next level. The model can also help you decide whether you’re comfortable with the trade-offs that come with moving further and further toward Pro-c status. The potential impact of your work increases as you progress toward Professional Creativity, but so do the expectations of those who will judge the value of your work.

The graphic below shows how the judges of the originality, impact, and value of your work change as you move from mini-c creativity to Big-C creativity. It starts out with you, the creator, and ends with the world.

Creativity and Context: Who judges originality, impact, and value?

In their article, Kaufman and Behgetto stress that mini-c, little-c, and Pro-c creativity are all expressions of everyday creativity that are available to everyone:

Our model reflects our belief that nearly all aspects of creativity can be experienced by nearly everyone. On an everyday basis, someone could try a brand new thing (such as fly fishing or making homemade ice cream or starting a video blog) and experience the new and personally meaningful experience of mini-c. Similarly, someone could continue to enjoy little-c creativity by trying to find a new way home from school or work, or playing a new song on the guitar, or acting in a local production of a musical. Many people will also experience every- day creativity at the Pro-c level. It is only the final stage, Big-C, a typically posthumous distinction, that is reserved for the elite few.

—James C. Kaufman and Ronald A. Behgetto, “Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity”

It’s important to remember that you can choose to work at different levels in different parts of your creative life. For example, if you make your living as a photographer and also play guitar, you can choose to compete at the Pro-C level as a photographer and at the min-c or little-c level as a guitar player.

We tend to focus on the story we want others to know about our creative ambitions and accomplishments, but the most important story is the story you tell yourself about your limitations, handicaps, and insignificance. The Four C model gives you a framework you can use to craft a nuanced story about your creative life—one that integrates all of your competing interests, ambitions, and obligations. It doesn’t demand that you’re all in or else you’re out… You can be a serious artist and a mom trying to find the right balance between your career ambitions and the needs of your family. You can focus on the little-c creative accomplishments that your current life allows and maintain your Pro-C ambitions—and know that you are seriously engaged in developing your creative life. You can judge your current work with empathy and kindness, holding yourself to standards that are appropriate to the level of creativity your current circumstances allow, and you can focus on the acquisition of the skills you’ll need to fully realize your ambitions when you have the time those ambitions require. his is what creative freedom is like when you break free from the archetypal myth of creative genius.